In 1958, William Higinbotham, an MIT physicist, created Tennis for Two on a large analogue computer and connected the oscilloscope screen for the annual visitor’s day at the Brookhaven National Laboratory in Upton, New York. However, it wasn’t until Atari released the very first arcade video game Pong in 1972 when video games started to become a popular medium nationwide. Video games, in the United States, historically have been a much-enjoyed form of relaxation and enjoyment amongst its players, however, it has also historically catered to a predominantly white demographic. An ad that Atari released for the Atari 2600 system featured a father trying to buy the Atari game system for his daughter next to him. It wasn’t advertised to one gender; it was a medium that could be used by anybody. At least by anyone who was white during that time, ignoring the research that black and brown communities were just as interested in video games as their white counterparts (Everett, 109-146). It created a perception that the internet was the white man’s domain, a belief that is still widely accepted amongst its users and gate-keepers.

GIRLS DON’T PLAY VIDEO GAMES, ESPECIALLY BROWN GIRLS

Unlike the toy industry, the video game industry did not rely on gender-specific marketing strategies in the ‘70s or ‘80s as “registration data was rarely returned” (Lien, 2013). Many studios simply tried to target everyone such as overworked adults, children, teenagers, parents. This strategy was perfectly fine until the video game crash of 1983. The number of games created was high, the quality, however, was very low. It wasn’t until 1985 when Nintendo made some deeply problematic strategic decisions which continue to haunt us today. Nintendo presented the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES) as a toy, in order to prevent the crash from happening again. Nintendo sought out people who played their games by publishing its own video game magazine, Nintendo Power, travelling to cities for tournaments and to get a glimpse of their players. “The numbers were in: More boys were playing video games than girls. Video games were about to be reinvented” (Lien, 2013). The deep-rooted social issue was that boys were being directed to science and technology while girls were directed to more ‘feminine’ options. A 1983 study found that women, “overall, had a positive view of arcades, but made up 20% of arcade players, mainly due to a lack of social support” (Kaplan, 93-98). Games like The Sims and King’s Quest had an overwhelming number of female players (Lien, 2013) but those Williams Electronics, Inc. Fly 6 statistics apparently did not matter when the video game industry decided to paint the canvas using a gendered – and white – brush. Video game companies capitalised on appealing to the ‘male gaze’: the degradation and sexualization of women. “Like the cover of the game Barbarian,

It wasn’t until 1983’s video game crash (Lien, 2013) that the video game scene morphed from entertainment that a family could Atari 2600 Commercials 5 enjoy together to being an all-boys club – an all-white boys club. “[Arcade games] were targeted at beer-drinking adults who were looking to wind down and socialize after work. Later, they spread to more family-friendly locations like malls, movie theatres, bowling alleys, and Chuck E. Cheese. But before they did, they were a mostly adult affair” (Lien, 2013). Simple games like Tetris and PinBall were just a cathartic way to release stress from work life. “Those games weren’t exactly female-targeted, but it was guys who were making them, and they were trying to make what they could with this technology” (Lien, 2013). There were some prominent women game designers during the ’70s and ’80s, obviously not as many as men. Games like King’s Quest, which was designed by Roberta Williams, were based on fairy tales and had a big following by women in their 30s. However, in the history of video games, there is hardly any mention of women of colour or people of colour. The female video game designers that are hailed and praised are mostly white women. Were there any women of colour who were interested in the same position back then AND given the opportunity?

Probably not.

which featured a scantily clad, buxom woman at the feet of a barely clothed man. She’s not a playable character in the game, of course” (Lien, 2013). Gendered marketing decisions meant that simple non-gendered games like Tetris had a more ‘masculine’ advertising campaign. After all, the first portable system from Nintendo was called Game Boy, not Game Girl. The decision, back then, to solely focus on one gender is part of the reason why the concept of ‘girls don’t play games’ still exists today. “Studies found that as early as kindergarten, children were already more likely to assume that video games were more appropriate for boys than girls, though computers were still viewed as gender-neutral until middle school” (Wilder et al. 215–28). As Marshal McLuhan states “...it is the medium that shapes and controls the scale and form of human association and action” (McLuhan, 11) so it shouldn’t be a surprise that men are trying to protect their ‘domain’ from ‘outsiders’. In How To Do Things With Videogames, Ian Bogost explored the problems of gatekeeping. Gatekeeping originally looked at media filtering content for the public. In the world of video games, the hardcore gamers filter the public and the medium of what is considered acceptable. Despite slowly seeing the blurring of lines in gender and sexuality, gaming communities are still adamant of keeping their outdated structures in place. Till this day, Internet technologies and virtual communities operate in a manner that benefits privileged identities: the straight white man (Daniels, 695). Similarly, till this day mainstream discussion of feminism and history of video games does not include the experiences of black and brown gamers.

“Till this day, Internet technologies and virtual communities operate in a manner that benefits privileged identities: the straight white man.”

A PERPETUATED, PRIVILEGED IDENTITY & ITS THREAT

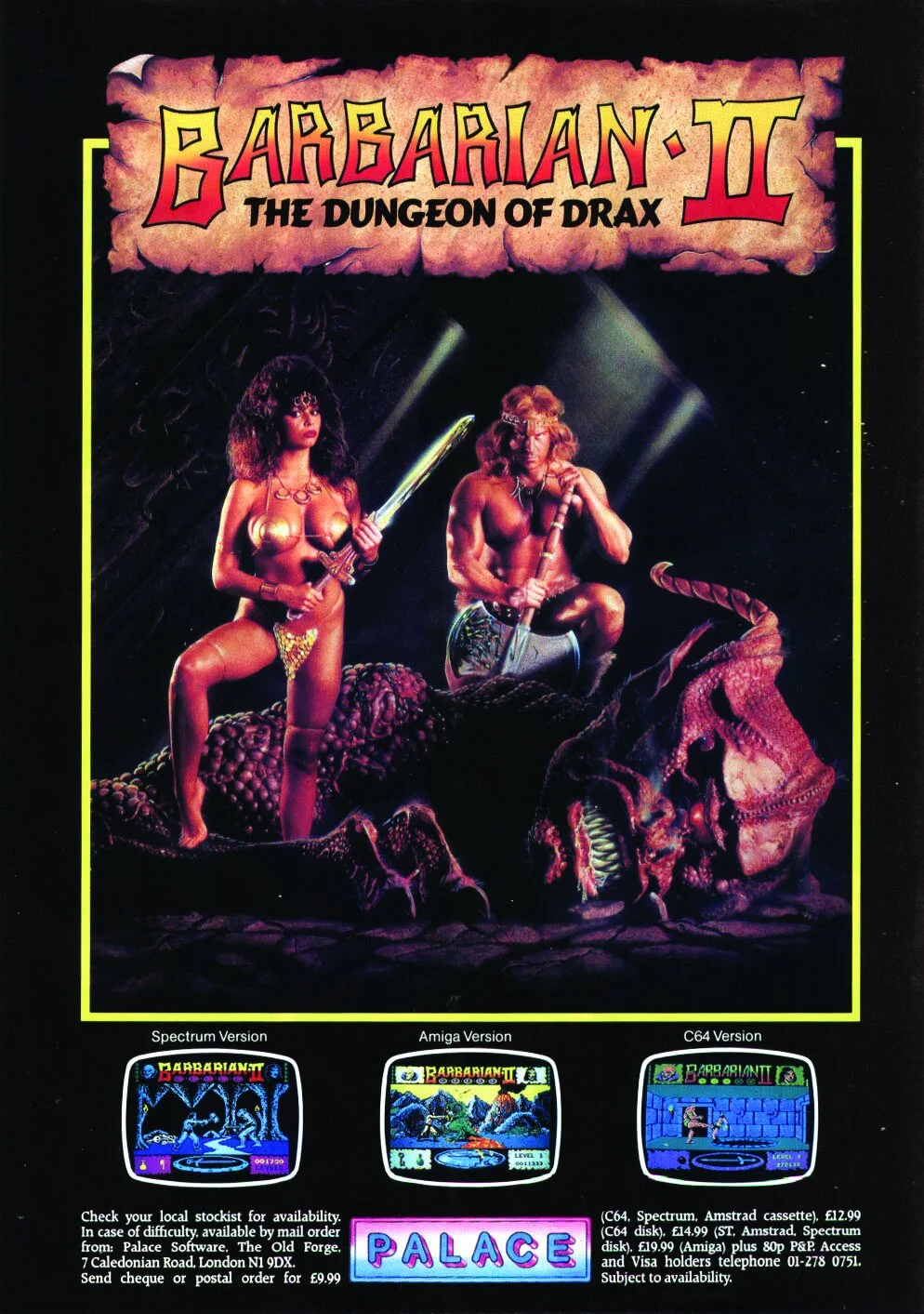

In June of 2019, E3 (Electronic Entertainment Expo), a premier trade event for the video game industry, showcased many upcoming video games from Microsoft, Bethesda Softworks, Nintendo, and more and was attended by almost 70 thousand people. At E3 presentations, out of all the presenters, only 21% of them were women, and out of all the games presented, only 5% of them featured women as the main character. In 2016, after winning a Team Fortress 2 game with the highest number of kills, a disgruntled man-child insisted that I, a ‘mere girl’, had cheated and threatened to get me banned. In a similar but worse vein, Eron Gjoni published a scandalous manifesto, during the summer of 2014, accusing his ex-girlfriend and indie game creator at the time, Zoe Quinn, of sleeping with Nathan Grayson, a writer for website Kotaku in order to receive a great review about her game Depression Quest. Famously hashtagged as #GamerGate, the conversation spiralled from the ethics of game journalism into harassment. Zoe Quinn and a gaming critic named Anita Sarkeesian were

both harassed horribly online. Anyone who was female and spoke out against this malicious turn of events was sent a series of death threats. “She said she was sad #GamerGate had made her, as a woman, suspicious and scared of fellow gamers. And she said she hoped the community could once again unite around everything that was good and beautiful about the medium that brought it together in the first place. Within an hour, her home address and other personal information had been posted in the post’s comments” (VanDerWerff, 2013). Though plenty of men have also opposed the way #GamerGate has affected women, not once were their home address and personal information posted on an online forum. According to a study, men gamers who lose are more likely to harass female gamers. “Low-status males that have the most to lose due to a hierarchical reconfiguration are responding to the threat female competitors pose” (Kasumovic et al. 2015). When a subculture has perpetuated a privileged identity, anyone who does not belong and shakes up the hierarchy is viewed as a threat.

Digging deeper into the intersectionality of oppressed gamers, research presented by the Pew Research Center shows that there are 83% African American and 65% Latinx teens who play video games however only 71% of Caucasians play video games. Despite the research, the industry does not reflect those playing its products as 68% of all game developers are white while only 12% are Asian, 5% are Latinx and a measly 1% are African/African-American. In the video game hierarchy, gamers of colour fall far below white and Asian female gamers. Gamers of colour, especially women of colour, have to deal with virtual racism as well as gendered bullying despite being behind a screen. Many multiplayer games have a voice chat feature to help with in-game coordination, however, “many players are linguistically profiled” (Gray, 119) and are attacked through profiling: “I believe I get called the N-word about 5 times a week if not more. ...They [are] cowards because I honestly believe that the losers that call me the N-word on Xbox would not have the courage to say it to my face” (Gray, 131). #GamerGate received a significant amount of traction, however, the mainstream feminist discourse of video games rarely looks deeply at the marginalisation of people of colour in these spaces. Feminist movements that involve tech spaces, such as Cyberfeminism and Technofeminism, look at the role of women in digital, mostly male-oriented, spheres but it has grossly ignored that white women and women of colour face different kinds of discrimination online and in the industry

visual representation of the statistics

“I believe I get called the N-word about 5 times a week if not more. ...They [are] cowards because I honestly believe that the losers that call me the N-word on Xbox would not have the courage to say it to my face”

COMBATING THE HEGEMONY OF ASSUMED WHITENESS

Historically, black and brown women were always left out of major feminist movements. In 1920, white women had the right to vote however, it wasn’t until 1965 that women of colour had the same voting rights as white women. “If you were a black woman in the early nineteenth century chances are you were a slave… you did not qualify as a ‘true’ woman…”(Dicker, 23-34). Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique which came out in 1963 looked at “the systemic sexism that taught women that their place was in the home and that if they were unhappy as housewives, it was only because they were broken and perverse” (Grady, 2018). However women of colour were already working, sometimes for white families, to support their families. No one spoke of “the forced sterilization of people of colour and people with disabilities” (Grady, 2018). In response, black women created the term womanist: “Womanist is to feminist as purple is to lavender” (Walker, 2011). In contemporary times, work of theorists like Kimberlé Crenshaw, who coined the term ‘intersectionality’ and Judith Butler, who argued the distinction between biological sex and gender, were the foundation for fighting “for trans rights as a fundamental part of intersectional feminism” (Grady, 2018).

women to exist on their own terms and to craft their own narratives” (Gray, 117). Taking inspiration from Donna Haraway’s Cyborg Manifesto “The cyborg is a kind of disassembled and reassembled, postmodern collective and personal self. This is the self feminists must code” (Haraway, 117– 58). Black Cyberfeminism is a critical framework that uses intersectionality and Cyberfeminism to push Black feminist theory in a virtual space. Gray utilizes the lack of discourse on black and brown bodies in virtual spaces to create a conversation on how the marginalised can combat the corrosive nature of straight white male power in this industry and employ tactics to craft out space for themselves in technological spheres. By focusing solely on gender, Cyberfeminism, Technofeminism, and other virtual feminisms fail to capture race and other intersections such as sexuality. Black Cyberfeminism captures the experiences, practices, and tactics that women of colour can use to combat the hegemony of “assumed whiteness” (Kolk et al. 225) within the digital sphere through three ways: (1) by exploring the social structural oppression of technology and virtual spaces; (2) by investigating intersecting oppressions experienced in virtual spaces; and (3) displaying the distinctness of the virtual feminist community (Gray, 2016).

Cyberfeminism explored the internet as a space that women would naturally thrive in despite technology being inherently seen as masculine. Sadie Plant, the person behind the term Cyberfeminism, argued that “women are naturally suited to using the Internet because women and the Internet are similar in nature—both, according to Plant, are non-linear, self-replicating systems concerned with making connections” (Consalvo, 2002). It was, however, intended for young, tech-savvy, middle-class, white women. What about women of colour who did not have access to these technologies and learning resources? Technofeminism advocated for women [read: white women] to work together to claim their space, but what about the intersection of race, sexuality AND being a woman? That did not come into play. Therefore, Kishonna Gray introduced the term ‘Black Cyberfeminism’ to “... build on Cyberfeminism and Black feminist thought to articulate the utility of a Black Cyberfeminist framework in examining the issues that continue to impede the progression of marginalised women in media, technology, virtuality, and physical spaces” (Gray, 117). It was created in response to the limitations of Cyberfeminism and Technofeminism and its take with the black identity and “… to begin the discussion of allowing

“[Kishonna] Gray utilizes the lack of discourse on black and brown bodies in virtual spaces to create a conversation on how the marginalised can combat the corrosive nature of straight white male power in this industry and employ tactics to craft out space for themselves in technological spheres.”

PLAY: A METHOD FOR GRANULAR, NON-INCREMENTAL CHANGE

In 2014, Ubisoft presented a new Assassin’s Creed game Unity - a multiplayer Assassin’s Creed game where up to four players can play 4 slightly different variations of a white man named Arno. Despite being set during the French Revolution where famously Charlotte Corday, nicknamed l’ange de l’assassinat, killed Jean-Paul Marat, one of the leaders of the Reign of Terror there is no mention of her or use of her in the game. The reason being that women were too difficult to animate as Ubisoft creative director Alex Amancio reported in an interview with Polygon. “It’s double the animations, it’s double the voices, all that stuff and double the visual assets,” Amancio said. “Especially because we have customizable assassins. It was really a lot of extra production work.” A feeble excuse that sparked outrage amongst the community as only two years prior Ubisoft released Assassin’s Creed 3: Liberation which featured a black female assassin as the main character. Assassin’s Creed 3: Liberation followed the life of a female 18th-century French-African assassin in Colonial America – who operated within Louisiana to free the slaves while eradicating the rival Templars, the corrupt organisation enslaving black families. The game was championed by many black gamers as being the very first time their story was represented through video games.

In games such as Mass Effect, Story of Seasons and The Sims where character creation is possible there still are barriers that prevent black and brown bodies from being represented. Many games like the ones mentioned above have the skin colours that match the respective players however just having brown skin colour as an option does not equal representation. “Hair texture is something that marks blackness,” Dr Yaba Blay, ethnographer and political science chair at North Carolina Central University, said in a phone interview with Mic. The distinct lack of black hair in these customizable creations poses a barrier between black and brown gamers and video game culture. Excuses like ‘it’s very difficult to code’ create the notion that only white and Asian accepted features are welcome in these spaces. However, gamers are trying to hack the system by designing custom black and brown mods for games like The Sims and releasing the code for free for other black gamers to use.

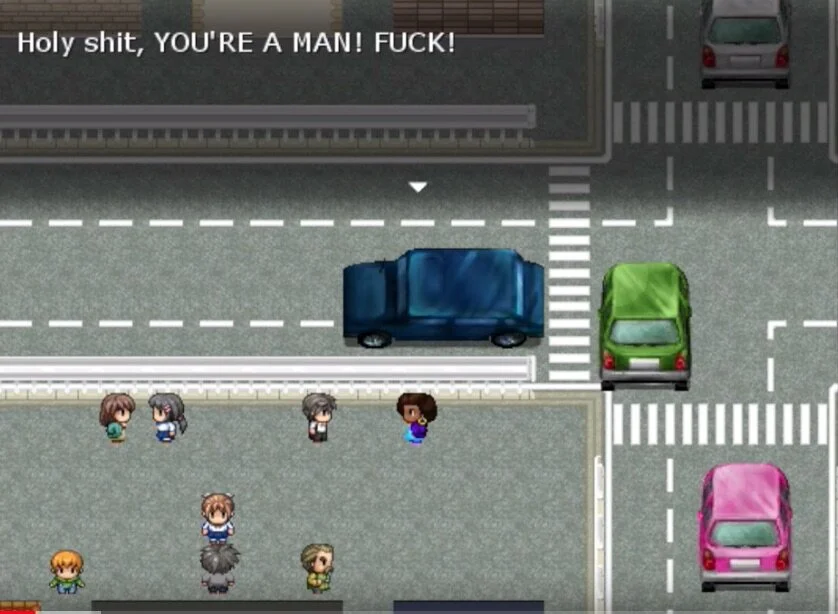

Mainichi

In her TED talk Using Play for Everyday Activism, Mattie Brice conveys the importance of play as a process for activism. “Creating play is manipulating environments, bodies, and social systems to reveal new possibilities (…) This outlook enables grassroots movements, where epic games continue the tradition of only the few engaging with social problems. [Play] is a method for granular, non-incremental change when epic change is impossible.” Diverging from the traditional view of play, Brice encourages ‘normative’ gamers and ‘divergent’ gamers to work together on an interpersonal level to combat the issues in the industry. Gameheads is a tech training program in Oakland, California where video game designers, developers and DevOps work with youth-of-colour from low-income neighbourhoods to guide and train them for the digital world. These companies/ non-profits are enlisting the help of gamers and engineers tobring more marginalised voices to the forefront of the game industries through small grassroots projects. Instead of trying to

create a conversation on gaming issues through ‘epic games’ or hoping that big-wig companies see the light, we should work on a more interpersonal level of change. Engagement on a one-to-one level solves local and personal issues as it allows incremental changes to be more meaningful and engaging. “The social problems we face aren’t purely mechanical, we have to work on changing culture, which can only happen with the participation of everyone inside of it” (Brice). By researching through design, Brice created Mainichi, a game that highlights her struggles as a black trans woman, for her cis-gendered best friend who “couldn’t fully grasp the nuances of [her] decision-making in spoken conversation”(Brice). The game went through the decisions that Matie had to make before leaving the house from how she presented herself to the impact of how others treated her. The game was then released to the general public and because of its intimate nature, it became widely popular and was featured at gaming events for four years.

“Instead of trying to create a conversation on gaming issues through ‘epic games’ or hoping that big-wig companies see the light, we should work on a more interpersonal level of change.”

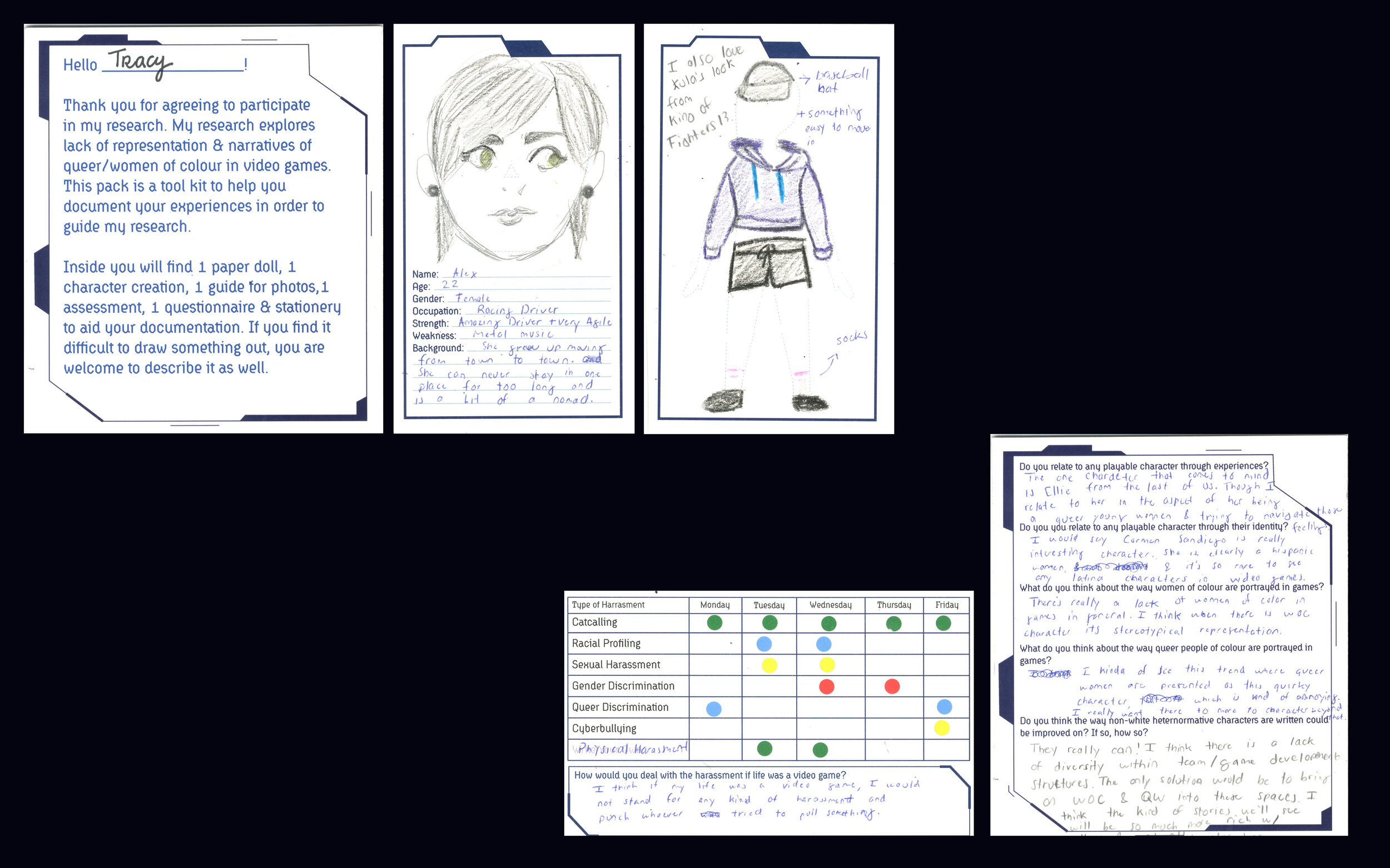

THE DIVERGENT & NORMATIVE COLLABORATION

Taking direction from Brice’s emphasis on grassroots efforts, this thesis worked with divergent gamers and normative creators to create a game that reflected the ‘distinctness of the virtual feminist community’. As someone who is part of both the normative –being Indian– and the divergent –being queer– it was important to consciously collaborate with my participants to create an experience that expanded beyond simply adding diversity into the medium. Utilising the third Black Cyberfeminist framework and Brice’s interpersonal method of change, this thesis used video game design and narrative as a platform to highlight the issues found in games and gaming structure to the public, gamers and aspiring game creators. It also hopes to create an initiative that allows minority gamer creators to be included in the conversation and creation of the games. To capture the ‘distinctiveness’, a cultural probe was conducted to garner information on women of colour gamers and their experiences with racism, sexism and misogyny both on and offline. The participants started with creating their own ideal video game character with statistics, backstories and visuals. In addition, participants were given a chart and questions to illustrate their experiences. The participants were specifically people of colour. Taking one participant, the game was built on their experience.

As we are critiquing single-player games, I decided to create a retro platform game called Paradise Abyss, much like Super Mario Bros, featuring a Afro-Latinx gamer and her experiences. Behind the scenes, Danny Dang agreed to be the developer and spearheaded the backend of the game via Unity Engine while I acted as the project manager and game designer. As a normative and divergent game designer, it was important to me that I gained the input from our gamer rather than to create a game ‘inspired’ by her. The character design and the physical personifications of the obstacles she experienced daily were presented to her and the feedback/changes I received were implemented. My role was to be the platform, as I had the skills and connections, for her to share her narrative and ideas.

Paradise Abyss is a platform game where the player takes control of our main girl, Doki, to survive the monsters that stood in her way. There are three planes: Paradise Skies, Material Ground, and Abyssal Caves. On Paradise Skies, Doki can receive magical mana and health to shoot the monsters by either collecting stars or allies. If she meets an ally she receives a temporary power-up for 10 seconds where the ally accompanies her to defeat the monsters. On Material Ground, she has to survive by defeating monsters like the ghostly K3 or Catler, personifications of racism and catcallers. In the Abyssal Caves, she has to defeat the Trolls and Stinger who charge after her. The goal of the game is to survive as long as possible with the help of her safe space and allies. Without allies or safe spaces, we are unable to deal with or defeat the monsters that are gatekeeping the medium.

“Without allies or safe spaces, we are unable to deal with or defeat the monsters that are gatekeeping the medium.”